Un erou american – Paul Revere

Paul Revere’s Ride

by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (1807-1882)

Listen my children and you shall hear

Of the midnight ride of Paul Revere,

On the eighteenth of April, in Seventy-five;

Hardly a man is now alive

Who remembers that famous day and year.

He said to his friend, “If the British march

By land or sea from the town to-night,

Hang a lantern aloft in the belfry arch

Of the North Church tower as a signal light,–

One if by land, and two if by sea;

And I on the opposite shore will be,

Ready to ride and spread the alarm

Through every Middlesex village and farm,

For the country folk to be up and to arm.”

Then he said “Good-night!” and with muffled oar

Silently rowed to the Charlestown shore,

Just as the moon rose over the bay,

Where swinging wide at her moorings lay

The Somerset, British man-of-war;

A phantom ship, with each mast and spar

Across the moon like a prison bar,

And a huge black hulk, that was magnified

By its own reflection in the tide.

Meanwhile, his friend through alley and street

Wanders and watches, with eager ears,

Till in the silence around him he hears

The muster of men at the barrack door,

The sound of arms, and the tramp of feet,

And the measured tread of the grenadiers,

Marching down to their boats on the shore.

Then he climbed the tower of the Old North Church,

By the wooden stairs, with stealthy tread,

To the belfry chamber overhead,

And startled the pigeons from their perch

On the sombre rafters, that round him made

Masses and moving shapes of shade,–

By the trembling ladder, steep and tall,

To the highest window in the wall,

Where he paused to listen and look down

A moment on the roofs of the town

And the moonlight flowing over all.

Beneath, in the churchyard, lay the dead,

In their night encampment on the hill,

Wrapped in silence so deep and still

That he could hear, like a sentinel’s tread,

The watchful night-wind, as it went

Creeping along from tent to tent,

And seeming to whisper, “All is well!”

A moment only he feels the spell

Of the place and the hour, and the secret dread

Of the lonely belfry and the dead;

For suddenly all his thoughts are bent

On a shadowy something far away,

Where the river widens to meet the bay,–

A line of black that bends and floats

On the rising tide like a bridge of boats.

Meanwhile, impatient to mount and ride,

Booted and spurred, with a heavy stride

On the opposite shore walked Paul Revere.

Now he patted his horse’s side,

Now he gazed at the landscape far and near,

Then, impetuous, stamped the earth,

And turned and tightened his saddle girth;

But mostly he watched with eager search

The belfry tower of the Old North Church,

As it rose above the graves on the hill,

Lonely and spectral and sombre and still.

And lo! as he looks, on the belfry’s height

A glimmer, and then a gleam of light!

He springs to the saddle, the bridle he turns,

But lingers and gazes, till full on his sight

A second lamp in the belfry burns.

A hurry of hoofs in a village street,

A shape in the moonlight, a bulk in the dark,

And beneath, from the pebbles, in passing, a spark

Struck out by a steed flying fearless and fleet;

That was all! And yet, through the gloom and the light,

The fate of a nation was riding that night;

And the spark struck out by that steed, in his flight,

Kindled the land into flame with its heat.

He has left the village and mounted the steep,

And beneath him, tranquil and broad and deep,

Is the Mystic, meeting the ocean tides;

And under the alders that skirt its edge,

Now soft on the sand, now loud on the ledge,

Is heard the tramp of his steed as he rides.

It was twelve by the village clock

When he crossed the bridge into Medford town.

He heard the crowing of the cock,

And the barking of the farmer’s dog,

And felt the damp of the river fog,

That rises after the sun goes down.

It was one by the village clock,

When he galloped into Lexington.

He saw the gilded weathercock

Swim in the moonlight as he passed,

And the meeting-house windows, black and bare,

Gaze at him with a spectral glare,

As if they already stood aghast

At the bloody work they would look upon.

It was two by the village clock,

When he came to the bridge in Concord town.

He heard the bleating of the flock,

And the twitter of birds among the trees,

And felt the breath of the morning breeze

Blowing over the meadow brown.

And one was safe and asleep in his bed

Who at the bridge would be first to fall,

Who that day would be lying dead,

Pierced by a British musket ball.

You know the rest. In the books you have read

How the British Regulars fired and fled,—

How the farmers gave them ball for ball,

From behind each fence and farmyard wall,

Chasing the redcoats down the lane,

Then crossing the fields to emerge again

Under the trees at the turn of the road,

And only pausing to fire and load.

So through the night rode Paul Revere;

And so through the night went his cry of alarm

To every Middlesex village and farm,—

A cry of defiance, and not of fear,

A voice in the darkness, a knock at the door,

And a word that shall echo for evermore!

For, borne on the night-wind of the Past,

Through all our history, to the last,

In the hour of darkness and peril and need,

The people will waken and listen to hear

The hurrying hoof-beats of that steed,

And the midnight message of Paul Revere.

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow was born on February 27, 1807 in Portland, Maine to Stephen Longfellow and Zilpan Wadsworth Longfellow. He was first enrolled in school at the age of three, and he had a love for literature early in his life. His father wanted him to become a lawyer, but Longfellow wanted to pursue his literary interests. He graduated from Bowdoin College in 1825, and was offered a position as the first professor of modern languages at Bowdoin. Longfellow accepted this offer, and began teaching in 1829, following an educational trip to Europe where he visited scholars in Spain, Italy, England, France and Germany. He created his own textbooks while teaching at Bowdoin, because, at the time, no others were available.

In 1831, Longfellow married Mary Storer Potter. Soon after his marriage, in 1834, Longfellow again traveled to Europe with his wife, in order to prepare for an appointment as professor at Harvard University. Mary Potter died in 1835 in Rotterdam and Longfellow returned to America alone. Longfellow was again married in 1841; his new wife was Frances Appleton. He resigned from Harvard in 1854 in order to dedicate all of his time to his writing. Some of Longfellow’s most popular works (The Song of Hiawatha and The Courtship of Miles Standish) were written during the years after he left Harvard. In 1861, Frances Appleton died as the result of serious burns recieved while sealing packages with matches and wax. Following his wife’s death, Longfellow again travelled to Europe before spending his last years in Cambridge. He died on March 24th, 1882.

Longfellow was awarded honorary degrees by both the University of Oxford and the University of Cambridge. He is considered to be the first professional poet in America and his later works, including Paul Revere’s Ride (1860), reflect his desire to establish an American Mythos.

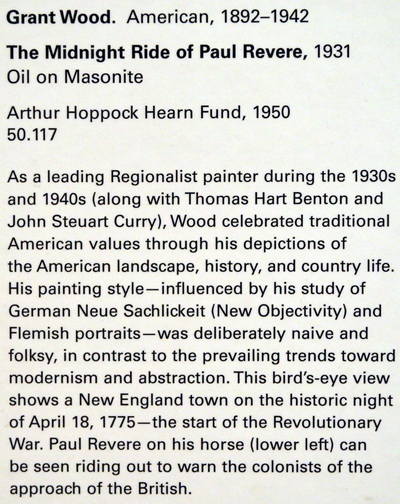

About Paul Revere’s Midnight Ride

On April 18, 1775, Paul Revere set out on his now famous ride from Boston, Massachusetts to Concord, Massachusetts. Revere was asked to make the journey by Dr. Joseph Warren of the Sons of Liberty, one of the first formal organizations of patriotic colonists. The purpose was to give warning to Samuel Adams, John Hancock (who were also members of the Sons of Liberty) and the other colonists that the British were preparing to march on Lexington.

Revere was taken by boat across the Charles River to Charleston, where he then borrowed a horse from a friend, Deacon John Larkin. Revere and a fellow patriot, Robert Newman, had previously arranged for signals to be given (lanterns in the tower of the North Church) so Revere would know how the British had begun their attack. This is where the famous phrase “one if by land, two if by sea” originated. While in Charleston, Revere and the Sons of Liberty saw that two lanterns had been hung in the North Church tower, indicating the British movement. Revere then left for Lexington.

On his way to Lexington, Revere stopped at each house to spread the word that the British troops would soon be arriving. Sometime around midnight, Revere arrived at the house of Reverend Jonas Clark, where Hancock and Adams were staying, and gave them his message. Soon after Revere’s message was delivered, another horseman sent on a different route by Dr. Warren, William Dawes, arrived. Revere and Dawes decided that they would continue on to Concord, Massachusetts, where the local militia had stockpiled weapons and other supplies for battle. Dr. Samuel Prescott, a third rider, joined Revere and Dawes.

On their way to Concord, the three were arrested by a patrol of British officers. Prescott and Dawes escaped almost immediately, but Revere was held and questioned at gunpoint. He was released after being taken to Lexington. Revere then went to the aid of Hancock and Adams, whom he helped escape the coming seige. He then went to a tavern with another man, Mr. Lowell, to retrieve a trunk of documents belonging to Hancock. At 5:00 a.m., as Revere and his associate emerged from the tavern, they saw the approaching British troops and heard the first shot of the battle fired on the Lexington Green. This gunshot of unknown origin, which caused the British troops to fire on the colonists, is known as “the shot heard round the world.”

Many believe Longfellow’s account of the Midnight Ride is inaccurate because he portrays Revere as a lone rider alerting the colonists. Longfellow also fails to mention that Revere was captured by British soldiers before he reached Concord. However, the literary creation of a folk hero named Paul Revere was inspiring to many, and the poem still reminds people of all ages what it means to be a patriot.

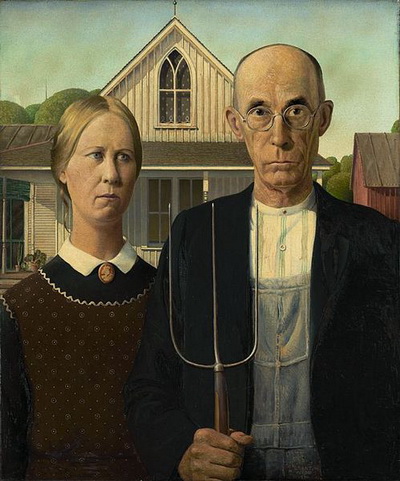

Grant DeVolson Wood (February 13, 1891 – February 12, 1942) was an American painter, born four miles east of Anamosa, Iowa. He is best known for his paintings depicting the rural American Midwest, particularly the painting American Gothic, an iconic image of the 20th century. Wood was an active painter from an extremely young age until his death, and although he is best known for his paintings, he worked in a large number of media, including lithography, ink, charcoal, ceramics, metal, wood and found objects.

Throughout his life he hired out his talents to many Iowa-based businesses as a steady source of income. This included painting advertisements, sketching rooms of a mortuary house for promotional flyers and, in one case, designing the corn-themed decor (including chandelier) for the dining room of a hotel. In addition, his 1928 trip to Munich was to oversee the making of the stained-glass windows he had designed for a Veterans Memorial Building in Cedar Rapids. The window was damaged during the 2008 flood and it is currently in the process of restoration. He again returned to Cedar Rapids to teach Junior High students after serving in the army as a camouflage painter.

Wood is most closely associated with the American movement of Regionalism that was primarily situated in the Midwest, and advanced figurative painting of rural American themes in an aggressive rejection of European abstraction.

Wood was one of three artists most associated with the movement. The others, John Steuart Curry and Thomas Hart Benton, returned to the Midwest in the 1930s due to Wood’s encouragement and assistance with locating teaching positions for them at colleges in Wisconsin and Kansas, respectively. Along with Benton, Curry, and other Regionalist artists, Wood’s work was marketed through Associated American Artists in New York for many years. Wood is considered the patron artist of Cedar Rapids, and his childhood country school is depicted on the 2004 Iowa State Quarter.