Andre Cadere – Roman sau nu?

Ia uitati ce minune de pictura am gasit tronand pe simezele de la Pompidou. Acum stau si ma intreb. Este Andre/Andrei Cadere roman sau nu? Pentru un artist vizual – deci care vorbeste limba universala a imaginii – e mai greu sau mai simplu sa fie revendicat de o natiune? Ma gandesc ca un scriitor de exemplu este mult mai marcat de limba in care s-a format. Si aduc ca argumente opiniile psihologilor care sustin ca gandim in cuvinte sau vorba filosofului din vechime care spunea ca “traim atatea vieti cate limbi cunoastem”. Cadere insa a trait mai mult in Franta, la Paris, si nu stiu sa fi dus prea tare dorul locurilor copilariei. Si-a asumat cu succes o atitudine de cetatean european. Asa ca va intreb inca odata: e Cadere roman sau nu? Si daca este, ce facem sa ni-l revendicam? (foto/text: Mihai Constantin)

Pun si eu la bataie in aceasta “dezbatere” un articol de Mark Godfrey aparut in Frieze Magazine (link aici)

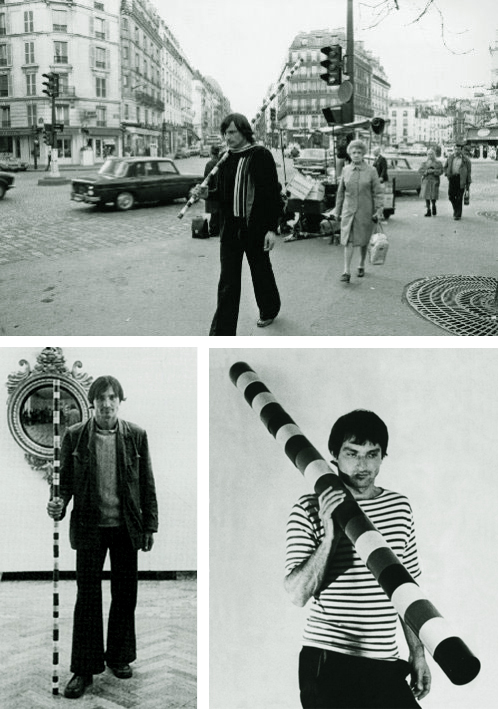

André Cadere was born in Poland, grew up in Romania and, before his early death from cancer in Paris in 1978, was a nomadic presence in the European art world. He was best known for his Barres de bois rond (Round Wooden Bars, 1970–78) – long poles made of coloured wooden cylindrical units. The colours on each rod were arranged according to a system, yet each stick contained one anomaly, confounding attempts to identify the system with ease. On a formal level his work certainly disrupted the traditional boundaries of painting and sculpture (disturbing the distinctions of these two media in a completely different way from Donald Judd’s ‘Specific Objects’), but in the context of 1970s’ art made in Paris the work was relatively traditional. (Just compare a hand-painted wooden object with a conical cut in a disused building by Gordon Matta-Clark.) Because his objects were ostensibly polite, it remains even more compelling just how challenging his practice was as a whole. This is a result of the ways in which Cadere chose to deploy these poles. Cadere was one of the first artists to realize that objects were inseparable from market and institutional contexts: half of his focus was on the systems of distribution in the art world. His Barres could be positioned in all sorts of relations to their surroundings (on walls, floors, propped between the two and so on), but he would also carry them around a number of outdoor locations and, most famously, into other people’s shows and openings, even when not invited.

The challenge of this retrospective – expertly curated by Karola Grässlin and Astrid Ihle – was to represent Cadere’s practice as a whole. Grässlin and Ihle tackled this by devoting generous space to documentation. A series of fascinating short films showed Cadere spraying lines of paint onto Parisian walls, using the same permutations developed in the Barres, and walking into posh New York galleries armed with his poles. Cabinets of photographs and postcards revealed his tempestuous dealings with Harald Szeemann prior to documenta 5; there was a list of London pubs at which he ‘displayed’ his work at the same time as he placed his Barres at the ICA during a show in 1976. The superb exhibition catalogue included a previously unpublished interview between the artist and Lynda Morris from the same year.

However useful these documents, what was really wonderful about the Baden-Baden exhibition was how the curators managed to convey the radicality of the work by positioning the objects within the classical building of the Kunsthalle in surprising ways. One Barre was tucked in the folds of the cornice just below the high ceiling; another nestled just above a skirting board; a third lay over a door frame. The curators paid respect to the classicism of Cadere’s installations (several works comprise eight individual Barres, placed so that the distance between them is equal to their length), but the positioning of some single rods in unexpected situations meant that each room felt quirky, its classical proportions slightly skewed.

Through this installation the curators revealed how Cadere managed to get under the skin of institutions, to upset order and charge space even while making very rigorous arrangements. This dynamic of order and disorder plays out on a material level in the charming objects themselves. However precise the positioning of the colours, the wood was manually carved and dented in places; none of the units is perfectly cylindrical; glue spills out between the gaps. Most Barres are slightly wonky; where the painted surfaces are scratched and chipped, it seems not to matter. Cadere, we surmise, positioned his work against what he perceived as the technophilia of Minimalism and Pop – the kind of work exhibited in the New York galleries that he would infiltrate. The Baden-Baden exhibition also revealed the quirkiness of his approach to colour. Although for the bulk of his career the colours of the units were really only there to show off the system, later on Cadere began to work in a more traditional way, creating harmonies and colour chords – placing mauves next to oranges and light blues.

The exhibition also suggested the various ways in which Cadere’s work relates to the body. The most obvious way is its handmade-ness: you never forget that the cylinders were sawn, sanded and stuck together by the artist. As for other kinds of relationships, though I would certainly not read Cadere’s Barres as abstracted figures (the way that some mistakenly read Barnett Newman’s zips), there is certainly something bodily about them. Many have bad posture, slouching against the walls and not keeping straight; those standing in the corners even call to mind the naughty-boy sculptures of Martin Kippenberger. It would appear that Cadere himself recognized the bodily in his work: two sticks, hung directly on the wall, were for him a kind of portrait of his friends Gilbert and George; his photographs of himself wearing stripy shirts and carrying the poles suggested another correspondence between his body and the Barres. The most important relation to the body, finally, comes from the fact that all these works were objects to be carried. In one of the last rooms in the show the curators displayed the only Barre that Cadere made that was too big for this: the exception proved the rule, and it was evident, finally, how the physical properties of the Barres (their weight and length) were predicated on the artist’s desire to use them as he did. What remains most interesting about Cadere’s work is this: at the same time as his deployment of the Barres diagnosed the exclusionism of the 1970s’ art system, his practice of showing work on streets, subway cars, etc, enacted the Utopian principle that handmade art works could be carried wherever the artist wanted – and be shown to whoever passed by.

Mark Godfrey