Balthus – Enigmatic, controversat, interesant

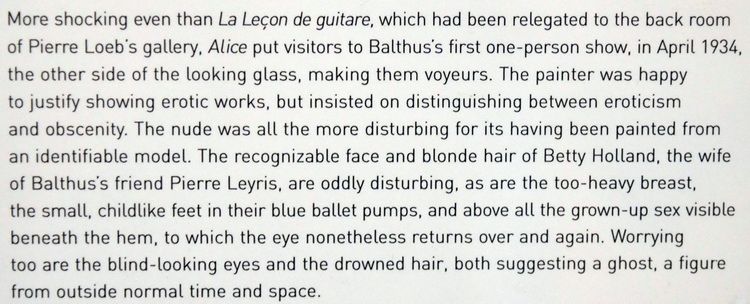

Balthasar Klossowski (or Kłossowski) de Rola (February 29, 1908 in Paris – February 18, 2001 in Rossinière, Switzerland), best known as Balthus, was an esteemed but controversial Polish-French modern artist.

Throughout his career, Balthus rejected the usual conventions of the art world. He insisted that his paintings should be seen and not read about, and he resisted any attempts made to build a biographical profile. A telegram sent to the Tate Gallery as it prepared for its 1968 retrospective of his works read: “NO BIOGRAPHICAL DETAILS. BEGIN: BALTHUS IS A PAINTER OF WHOM NOTHING IS KNOWN. NOW LET US LOOK AT THE PICTURES. REGARDS. B.”[1]

Early years

In his formative years his art was sponsored by Rainer Maria Rilke, Maurice Denis, Pierre Bonnard and Henri Matisse. His father, Erich Klossowski, a noted art historian who wrote a monograph on Daumier, and his mother Elisabeth Dorothea Spiro (known as the painter Baladine Klossowska) were part of the cultural elite in Paris. Balthus’s older brother, Pierre Klossowski, was a philosopher and writer influenced by theology and the works of the Marquis de Sade. Among the visitors and friends of the Klossowskis were famous writers such as André Gide and Jean Cocteau, who found some inspiration for his novel Les Enfants Terribles (1929) in his visits to the family.

In 1921 Mitsou, a book which included forty drawings by Balthus, was published. It depicted the story of a young boy and his cat, with a preface by Balthus’s mentor, the Bohemian-Austrian poet Rainer Maria Rilke (1875-1926) who at the time was his mother’s lover. The theme of the story foreshadowed his lifelong fascination with cats, which resurfaced with his self-portrait as The King of Cats (1935). In 1926 he visited Florence, copying frescos by Piero della Francesca, which inspired another early ambitious work by the young painter: the tempera wall paintings of the Protestant church of the Swiss village of Beatenberg (1927). From 1930 to 1932 he lived in Morocco, was drafted into the Moroccan infantry in Kenitra and Fes, worked as a secretary, and sketched his painting La Caserne (1933).

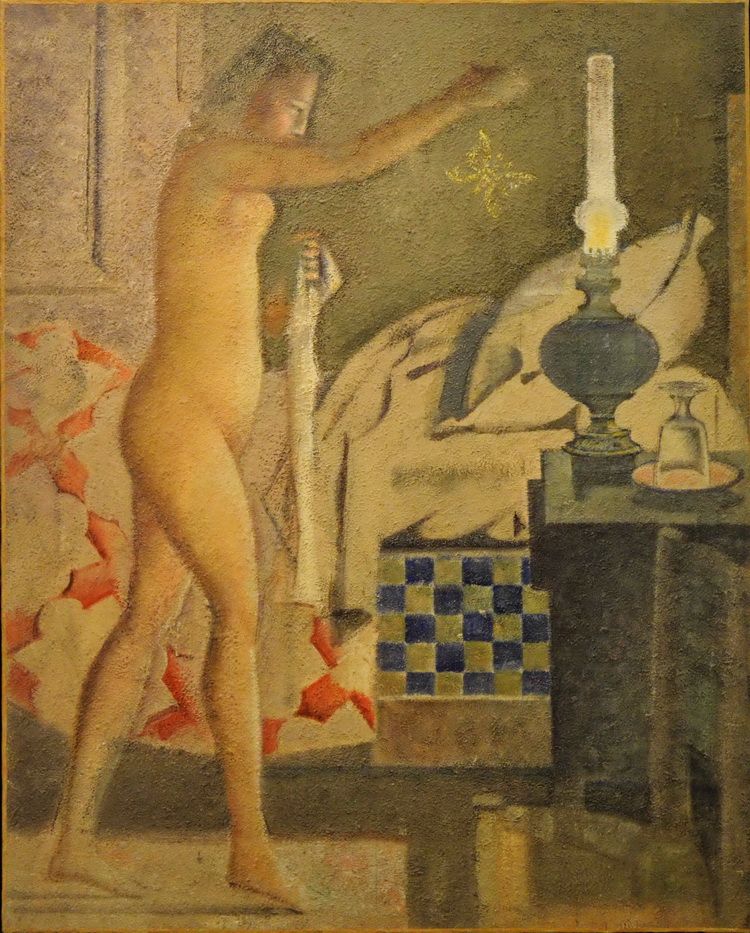

Moving in 1933 into his first Paris studio at the Rue de Furstemberg and later another at the Cour de Rohan, Balthus showed no interest in modernist styles such as Cubism. His paintings often depicted pubescent young girls in erotic and voyeuristic poses. One of the most notorious works from his first exhibition in Paris was The Guitar Lesson (1934), which caused controversy due to its sexually explicit depiction of a girl arched on her back over the lap of her female teacher, whose hands are positioned on the girl as for playing the guitar: one near her exposed crotch, another grasping her hair. Other important works from the same exhibition included La Rue (1933), La Toilette de Cathy (1933) and Alice dans le miroir (1933).[2]

In 1937 he married Antoinette de Watteville, who was from an old and influential aristocratic family from Bern. He had met her as early as 1924, and she was the model for the aforementioned La Toilette and for a series of portraits. Balthus had two children from this marriage, Thaddeus and Stanislas (Stash) Klossowski, who recently published books on their father, including the letters by their parents.

Early on his work was admired by writers and fellow painters, especially by André Breton and Pablo Picasso. His circle of friends in Paris included the novelists Pierre Jean Jouve, Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, Joseph Breitbach, Pierre Leyris, Henri Michaux, Michel Leiris and René Char, the photographer Man Ray, the playwright and actor Antonin Artaud, and the painters André Derain, Joan Miró and Alberto Giacometti (one of the most faithful of his friends). In 1948, another friend, Albert Camus, asked him to design the sets and costumes for his play L’Etat de Siège (The State of Siege, directed by Jean-Louis Barrault). Balthus also designed the sets and costumes for Artaud’s adaptation for Percy Bysshe Shelley’s The Cenci (1935), Ugo Betti’s Delitto all’isola delle capre (Crime on Goat-Island, 1953) and Barrault’s adaptation of Julius Caesar (1959–1960).

Champrovent to Chassy

In 1940, with the invasion of France by German forces, Balthus fled with his wife Antoinette to Savoy to a farm in Champrovent near Aix-les-Bains, where he began work on two major paintings: Landscape near Champrovent (1942–1945) and The Living Room (1942). In 1942, he escaped from Nazi France to Switzerland, first to Bern and in 1945 to Geneva, where he made friends with the publisher Albert Skira as well as the writer and member of the French Resistance, André Malraux. Balthus returned to France in 1946 and a year later traveled with André Masson to Southern France, meeting figures such as Picasso and Jacques Lacan, who eventually became a collector of his work. With Adolphe Mouron Cassandre in 1950, Balthus designed stage decor for a production of Mozart’s opera Così fan tutte in Aix-en-Provence. Three years later he moved into the Chateau de Chassy in the Morvan, living with his niece Frédérique Tison and finishing his large-scale masterpieces La Chambre (The Room 1952, possibly influenced by Pierre Klossowski’s novels) and Le Passage du Commerce Saint-André (1954).

As international fame grew with exhibitions in the gallery of Pierre Matisse (1938) and the Museum of Modern Art (1956) in New York City, he cultivated the image of himself as an enigma. In 1964, he moved to Rome where he presided over the Villa de Medici as director (appointed by the French Minister of Culture André Malraux) of the French Academy in Rome, and made friends with the filmmaker Federico Fellini and the painter Renato Guttuso.

In 1977 he moved to Rossinière, Switzerland. That he had a second, Japanese wife Setsuko Ideta whom he married in 1967 and was thirty-five years his junior, simply added to the air of mystery around him (he met her in Japan, during a diplomatic mission also initiated by Malraux). A son, Fumio, was born in 1968 but died two years later.

The photographers and friends Henri Cartier-Bresson and Martine Franck (Cartier-Bresson’s wife), both portrayed the painter and his wife and their daughter Harumi (born 1973) in his Grand Chalet in Rossinière in 1999.

Balthus was one of the few living artists to be represented in the Louvre, when his painting The Children (1937) was acquired from the private collection of Pablo Picasso.[3][4]

Prime Ministers and rock stars alike attended the funeral of Balthus. Bono, lead-singer of U2, sang for the hundreds of mourners at the funeral, including the President of France, the Prince Sadruddhin Aga Khan, supermodel Elle Macpherson, and Cartier-Bresson.

Style and themes

Balthus’s style is primarily classical. His work shows numerous influences, including the writings of Emily Brontë, the writings and photography of Lewis Carroll, and the paintings of Masaccio, Piero della Francesca, Simone Martini, Poussin, Jean Etienne Liotard, Joseph Reinhardt, Géricault, Ingres, Goya, Jean-Baptiste Camille Corot, Courbet, Edgar Degas, Félix Vallotton and Paul Cézanne. Although his technique and compositions were inspired by pre-renaissance painters, there also are eerie intimations of contemporary surrealists like de Chirico. Painting the figure at a time when figurative art was largely ignored, he is widely recognised as an important 20th century artist.

Many of his paintings show young girls in an erotic context. Balthus insisted that his work was not erotic but that it recognized the discomforting facts of children’s sexuality.

Ancestral debates

Balthus’s father, Erich, was born to a noble Polish family (szlachta) of the Rola coat of arms, that lived in Prussia. This was evidently the reason for his son Balthus, to add, later, “de Rola” to his family name Klossowski, which was in szlachta tradition (if he had lived in Poland, the arrangement of his last name would have been Rola-Kłossowski or Kłossowski h. Rola.) The artist was very conscious of his Polish ancestry and the Rola arms was embroidered onto many of his kimono, in the style of Japanese kamon.

According to most biographies, Balthus denied having any ethnic Jewish heritage, claiming that biographers had confused his mother’s true ancestry. In Balthus: A Biography, Nicholas Fox Weber, who is Jewish, attempts to find common ground while interviewing the painter by bringing up a biographical note stating that his mother was Jewish. Balthus replied, “No, sir, that is incorrect,” and explained: “One of my father’s best friends was a painter called Eugen Spiro, who was the son of a cantor. My mother was also called Spiro, but came apparently from a Protestant family in the south of France. One of the Midi Spiros – one of the ancestors – went to Russia. They were likely of Greek origin. We called Eugen Spiro “Uncle” because of the close relationship, but he was not my real uncle. The Protestant Spiros are still in the south of France.”[citation needed]

Balthus continued by saying he did not think it was tasteful to forcefully correct these errors, given his many Jewish friends. Nicholas Fox Weber concludes in his biography that Balthus was lying about this “biographical error,” though the exact reasoning behind this was never explained. Weber states that the name “Spiro” is only a Greek given name, though this is incorrect, as the personal name serves equally as a surname.[5] Balthus consistently repeated that if he, in fact, was Jewish, he would have no problem with it. In support of Weber’s view, Balthus did make dubious claims about his ancestry before, once claiming he was descended from Lord Byron on his father’s side.[citation needed]

According to Weber, Balthus would frequently add to the story of his mother’s ancestry, saying that she was also related to the Romanov, Narischkin, and lesser known Raginet families among others, though conceding Balthus never claimed his mother’s side was from a straight unmixed lineage. Despite the sensationalism with which Weber says he told these stories and the method in which Weber presents Balthus’s claims, Balthus never saw himself as contradictory. The true extent of what Balthus was saying for artistic effect and what he was saying in earnest is unknown as he did not stick seriously to all his claims. Weber never interviewed Pierre Klossowski, the painter’s brother, in order to confirm or deny their mother’s ancestry. Weber did, however, present a quote by Baladine’s lover, the poet Rainer Maria Rilke, in which Rilke states that the Spiros were descended from one of the richest Sephardic-Spanish families. In a seemingly conclusionary note, Weber writes: “The artist neglected, however, to tell me that, in the most miserable of ironies, Fumio (Balthus’s son) suffered from Tay-Sachs disease.”[citation needed] Weber holds this up as evidence that Balthus was lying about not having Jewish ancestry, given Tay-Sachs is a heavily Ashkenazic-Jewish disease. This, of course, conflicts with Rilke’s report of the Spiros being Sephardic, which Weber later says was a “Rilke embellishment” and also brings up the relevance of the preponderance of Japanese infantile Tay-Sachs, since Balthus’s wife was Japanese.

His work has strongly influenced several contemporary artists; among them Jan Saudek, Will Barnet, Duane Michals, John Currin, and Emile Chambon.[citation needed]

He has also influenced the filmmaker Jacques Rivette of the French New Wave, whose film Hurlevent (1985) was inspired by Balthus’s drawings made at the beginning of the 1930s: “Seeing as he’s a bit of an eccentric and all that, I am very fond of Balthus (…) I was struck by the fact that Balthus enormously simplified the costumes and stripped away the imagery trappings (…)”.[6]

A reproduction of Balthus’s Girl at a Window (a painting from 1957) prominently appears in François Truffaut’s film Domicile Conjugal (Bed & Board, 1970). The two principal characters, Antoine Doinel (Jean-Pierre Léaud) and his wife Christine (Claude Jade), are arguing. Christine takes down from the wall a small drawing of about 25×25 cm and gives it to her husband: Christine: “Here, take the small Balthus.” Antoine: “Ah, the small Balthus. I offered it to you, it’s yours, keep it.”

Harold Budd’s album The White Arcades includes a track titled “Balthus Bemused by Color.”

Robert Dassanowsky’s book Telegrams from the Metropole: Selected Poems 1980-1998 includes “The Balthus Poem.”

South African novelist Christopher Hope wrote My Chocolate Redeemer around a painting by Balthus, The Golden Days (1944), which appears on the book jacket.

Stephen Dobyns’ book The Balthus Poems (Atheneum, 1982) describes individual paintings by Balthus in 32 narrative poems.

His widow, Setsuko Klossowska de Rola, heads the Balthus Foundation established in 1998.

Films on Balthus

Damian Pettigrew, Balthus Through the Looking Glass (72′, Super 16, PLANETE/CNC/PROCIREP, 1996). Documentary on and with Balthus filmed at work in his studio and in conversation at his Rossinière chalet. Shot over a 12-month period in Switzerland, Italy, France and the Moors of England.

Balthus by Damian Pettigrew (1996)

Balthus by Damian Pettigrew (1996)

Foto: Mihai Constantin (in Centrul Pompidou)