Sonia si Robert Delaunay – O poveste de dragoste si culoare

Romanticul din mine, atunci cand castiga temporar intaietate, se lasa coplesit de povesti ale cuplurilor din lumea artei. Sonia si Robert Delaunay au o astfel de poveste dar imi vin in minte si Georgia O’Keeffe si Alfred Stieglitz, Gaston Lachaise si Isabel Nagle sau Theodor Aman si Ana Dorobantu si cate or mai fi prin lume si istorie. Ce urmeaza este insa biografia – o sa vedeti, savuroasa – a sotilor Delaunay pe care i-am remarcat bine reprezentati si promovati in muzeele pariziene. Lucrarile de aici sunt facute de mine in Centrul Pompidou iar textele sunt preluate de pe onor Wikipedia. (Mihai Constantin)

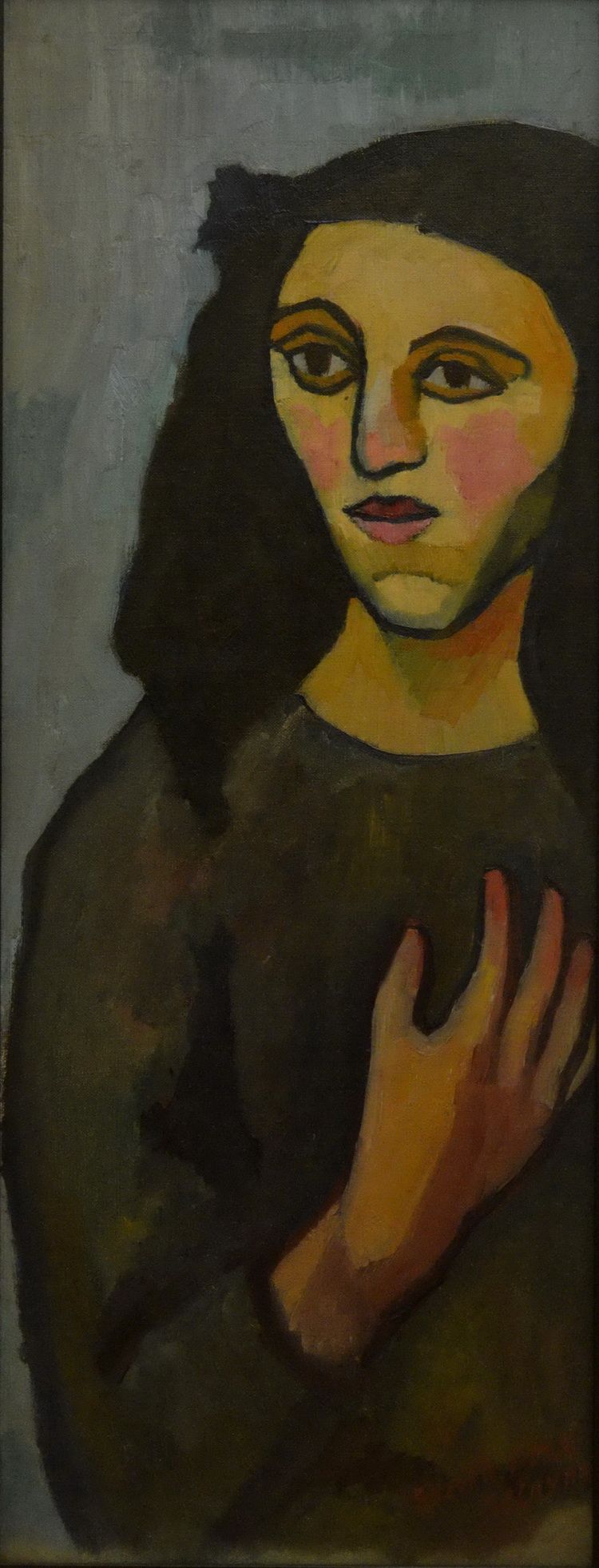

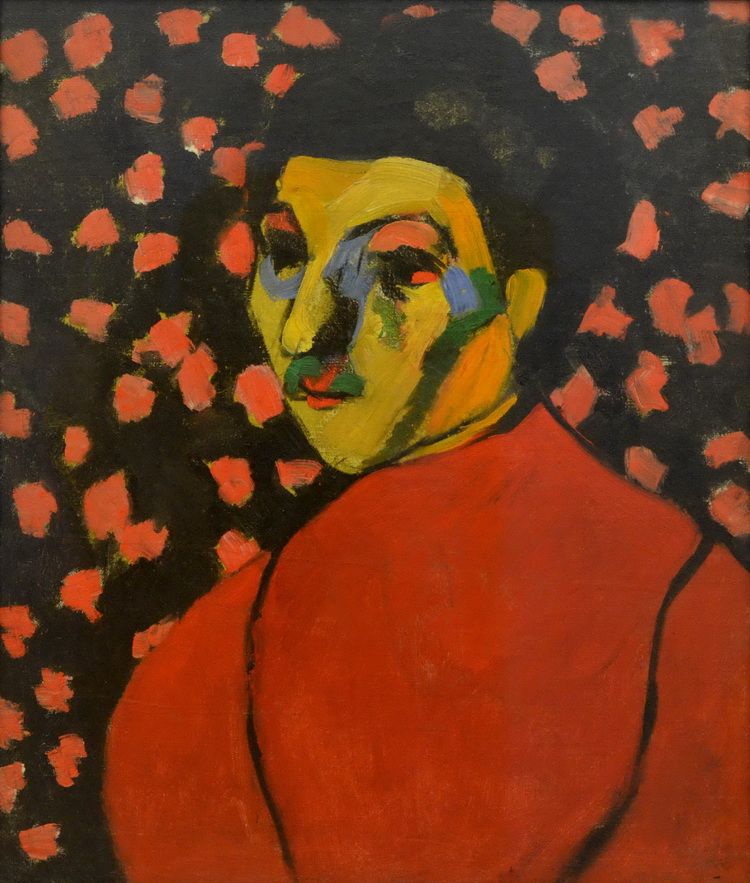

Sonia Delaunay (November 14, 1885 – December 5, 1979) was a Jewish-French artist who, with her husband Robert Delaunay and others, cofounded the Orphism art movement, noted for its use of strong colours and geometric shapes. Her work extends to painting, textile design and stage set design. She was the first living female artist to have a retrospective exhibition at the Louvre in 1964, and in 1975 was named an officer of the French Legion of Honor.

Sonia Delaunay (November 14, 1885 – December 5, 1979) was a Jewish-French artist who, with her husband Robert Delaunay and others, cofounded the Orphism art movement, noted for its use of strong colours and geometric shapes. Her work extends to painting, textile design and stage set design. She was the first living female artist to have a retrospective exhibition at the Louvre in 1964, and in 1975 was named an officer of the French Legion of Honor.

Her work in modern design included the concepts of geometric abstraction, the integration of furniture, fabrics, wall coverings, and clothing. Early life (1885-1904)

Early life (1885-1904)

Sarah Ilinitchna Stern was probably born in Gradizhsk, then in the Russian Empire, today in Poltava Oblast in Ukraine, on 14 November 1885.[1] Her father was foreman of a nail factory.[2] At a young age she moved to St. Petersburg, where she was cared for by her mother’s brother, Henri Terk. Henri, a successful and affluent Jewish lawyer, and his wife Anna wanted to adopt her but her mother would not allow it. Finally in 1890 she was adopted by the Terks.[3] She assumed the name Sonia Terk and received a privileged upbringing with the Terks, they spent their summers in Finland and traveled widely in Europe introducing Sonia to art museums and galleries. When she was 16 she attended a well-regarded secondary school in St. Petersburg, where her skill at drawing was noted by her teacher. When she was 18, at her teacher’s suggestion, she was sent to art school in Germany where she attended the Academy of Fine Arts in Karlsruhe. She studied in Germany until 1905 when she decided to move on to Paris.[4]

When she arrived in Paris she enrolled at the Académie de la Palette in Montparnasse. Unhappy with the mode of teaching, which she thought was too critical, she spent less time at the Académie and more time in galleries around Paris. Her own work during this period was strongly influenced by the art she was viewing including the post-impressionist art of Van Gogh, Gauguin and Henri Rousseau and the fauves including Henri Matisse and Derain. During her first year in Paris she met, and in 1908 married, German homosexual art gallery owner Wilhelm Uhde. Little is known about their union, but it is assumed to have been a marriage of convenience to escape the demands of her parents, who disliked her artistic career, for her to return to Russia.[5] Sonia gained entrance into the art world via exhibitions at Uhde’s gallery and benefitted from his connections, and Uhde masked his homosexuality through his public marriage to Sonia.[citation needed]

Comtesse de Rose, mother of Robert Delaunay, was a regular visitor to Uhde’s gallery, sometimes accompanied by her son. Sonia met Robert Delaunay in early 1909. They became lovers in April of that year and it was decided that she and Uhde should divorce. The divorce was finalised in August 1910.[6] Sonia was pregnant and she and Robert married on November 15, 1910. Their son Charles was born on January 18, 1911.[7] They were supported by an allowance sent from Sonia’s aunt in St. Petersburg.[8]

Sonia said about Robert: “In Robert Delaunay I found a poet. A poet who wrote not with words but with colours“.[7]

Orphism (1911-1913)

The last section of La prose du Transsibérien et de la Petite Jehanne de France, 1913

In 1911, Sonia made a patchwork quilt for Charles’s crib, which is now in the collection of the Musée National d’Art Moderne in Paris. This quilt was created spontaneously and uses geometry and color.

“About 1911 I had the idea of making for my son, who had just been born, a blanket composed of bits of fabric like those I had seen in the houses of Russian peasants. When it was finished, the arrangement of the pieces of material seemed to me to evoke cubist conceptions and we then tried to apply the same process to other objects and paintings.” Sonia Delaunay[9]

Contemporary art critics recognize this as the point where she moved away from perspective and naturalism in her art. Around the same time, cubist works were being shown in Paris and Robert had been studying the color theories of Michel Eugène Chevreul; they called their experiments with color in art and design simultanéisme. Simultaneous design occurs when one design, when placed next to another, affects both; this is similar to the theory of colors (Pointillism, as used by e.g. Georges Seurat) in which primary color dots placed next to each other are “mixed” by the eye and affect each other. Sonia’s first large-scale painting in this style was Bal Bullier (1912–13), a painting known for both its use of color and movement.

The Delaunays’ friend, the poet and art critic Guillaume Apollinaire, coined the term Orphism to describe the Delaunays’ version of cubism in 1913. It was through Apollinaire that in 1912 Sonia met the poet Blaise Cendrars who was to become her friend and collaborator. Sonia described in an interview that the discovery of Cendrars’ work “gave me [her] a push, a shock.”[10] She illustrated Cendrars’ poem La prose du Transsibérien et de la Petite Jehanne de France (Prose of the Trans-Siberian and of Little Jehanne of France) about a journey on the Trans-Siberian Railway, by creating a 2m-long accordion-pleated book. Using simultaneous design principles the book merged text and design. The book, which was sold almost entirely by subscription, created a stir amongst Paris critics. The simultaneous book was later shown at the Autumn Salon in Berlin in 1913, along with paintings and other applied artworks such as dresses, and it is said[who?] that Paul Klee was so impressed with her use of squares in her binding of Cendrars’s poem that they became an enduring feature in his own work.

Spanish and Portuguese years (1914-1920)

The Delaunays travelled to Spain in 1914, staying with friends in Madrid. At the outbreak of the First World War in 1914 Sonia and Robert were staying in Fontarabie, with their son still in Madrid. They decided not to return to France.[11] In August 1915 they moved to Portugal where they shared a home with Samuel Halpert and Eduardo Viana.[12] With Viana and their friends Amadeo de Souza-Cardoso, whom the Delaunays had already met in Paris,[13] and José de Almada Negreiros they discussed an artistic partnership.[14] In Portugal she painted Marché au Minho (the market at Minho, 1916), which she later says was “inspired by the beauty of the country”.[15] Sonia had a solo exhibition in Stockholm (1916).

The Russian Revolution brought an end to the financial support Sonia received from her family in Russia, and a different source of income was needed. In 1917 the Delaunays met Sergei Diaghilev in Madrid. Sonia designed costumes for his production of Cleopatra (stage design by Robert Delaunay) and for the performance of Aida in Barcelona. In Madrid she decorated the Petit Casino (a nightclub) and founded Casa Sonia, selling her designs for interior decoration and fashion, with a branch in Bilbao.[16] She was the center of a Madrid Salon.[17]

Sonia Delaunay travelled to Paris twice in 1920 looking for opportunities in the fashion business,[18] and in August she wrote a letter to Paul Poiret stating she wants to expand her business and include some of his designs. Poiret declined, claiming she has copied designs from his Ateliers de Martine and is married to a French deserter (Robert).[19] Galerie der Sturm in Berlin showed works by Sonia and Robert from their Portuguese period the same year.[20]

Sonia, Robert and their son Charles returned to Paris permanently in 1921 and moved into Boulevard Malesherbes 19.[21] The Delaunay’s most acute financial problems were solved when they sold La Charmeuse de serpents (the snake charmer) to Jacques Doucet.[22] Sonia Delaunay made clothes for private clients and friends, and in 1923 created fifty fabric designs using geometrical shapes and bold colours, commissioned by a manufacturer from Lyon.[23] Soon after, she started her own business and simultané became her registered trademark.

For the 1923 staging of Tristan Tzaras play Le Cœur à Gaz she designed the set and costumes.[24] In 1924 she opened a fashion studio together with Jacques Heim. Her customers included Nancy Cunard, Gloria Swanson, Lucienne Bogaert and Gabrielle Dorziat.[25]

With Heim she had a pavilion at the 1925 Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes, called boutique simultané.[26] Sonia Delaunay gave a lecture at the Sorbonne[27] on the influence of painting on fashion.

“If there are geometric forms, it is because these simple and manageable elements have appeared suitable for the distribution of colors whose relations constitute the real object of our search, but these geometric forms do not characterize our art. The distribution of colors can be effected as well with complex forms, such as flowers, etc. … only the handling of these would be a little more delicate.”

Sonia Delaunay, speaking at the Sorbonne, 1927[28]

Sonia designed costumes for two films: Le Vertige directed by Marcel L’Herbier and Le p’tit Parigot, directed by René Le Somptier,[29] and designed some furniture for the set of the 1929 film Parce que je t’aime (Because I love you).[30] The Great Depression caused a decline in business. After closing her business, Sonia Delaunay returned to painting, but she still designed for Jacques Heim, Metz & Co and private clients. She said “the depression liberated her from business”.[31] 1935 the Delaunays moved to rue Saint-Simon 16.[32]

By the end of 1934 Sonia was working on designs for the 1937 Exposition Internationale des Arts et Techniques dans la Vie Moderne, for which she and Robert worked together on decorating two pavilions: the Pavillon des Chemins de Fer and the Palais de l’Air. Sonia however did not want to be part of the contract for the commission, but chose to help Robert if she wanted. She said “I am free and mean to remain so.”[33] The murals and painted panels for the exhibition were executed by fifty artists including Albert Gleizes, Léopold Survage, Jacques Villon, Roger Bissière and Jean Crotti.[34]

Robert Delaunay died of cancer in October 1941.

Later life (1945-1979)

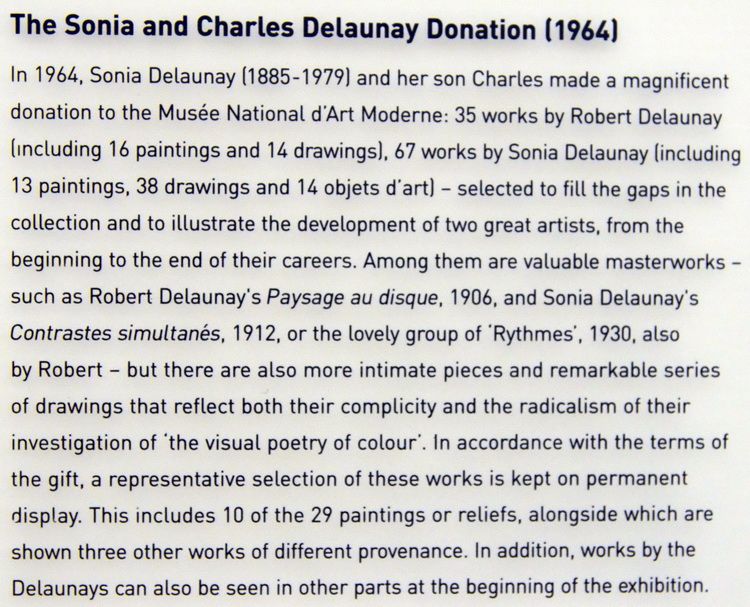

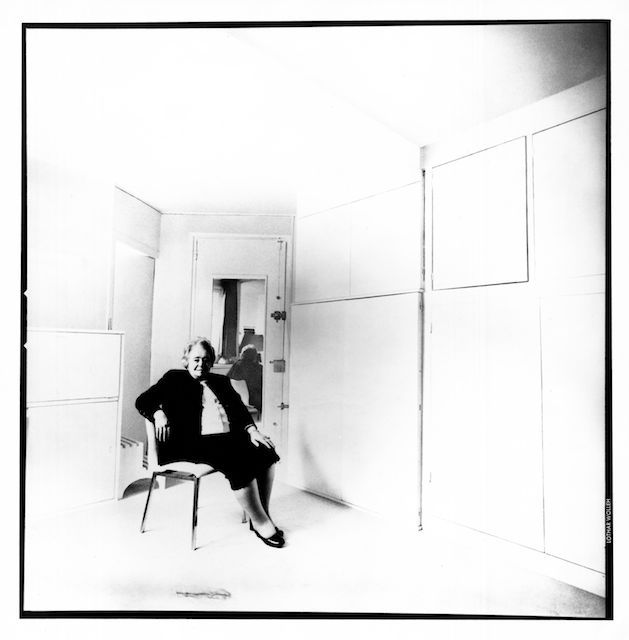

After the second world war, Sonia was a board member of the Salon des Réalités Nouvelles for several years.[35] Sonia and her son Charles in 1964 donated 114 works by Sonia and Robert to the Musée National d’Art Moderne.[36] Alberto Magnelli told her “she and Braque were the only living painters to have been shown at the Louvre”.[37] In 1966 she published Rythmes-Couleurs (color-rhythms), with 11 of her gouaches reproduced as pochoirs and texts by Jacques Damase,[38] and in 1969 Robes poèmes (poem-dresses), also with texts by Jacques Damase containing 27 pochoirs.[39] For Matra, she decorated a Matra 530. In 1975 Sonia was named an officer of the French Legion of Honor. Her autobiography, Nous irons jusqu’au soleil (We shall go up to the sun) was published in 1978.[40]

Sonia Delaunay died December 5, 1979, in Paris, aged 94. She was buried in Gambais, next to Robert Delaunay’s grave.[41]

Her work in modern design included the use of geometric abstraction and the integration of furniture, fabrics, wall coverings and clothing. Jazz expert Charles Delaunay is her son.

Legacy

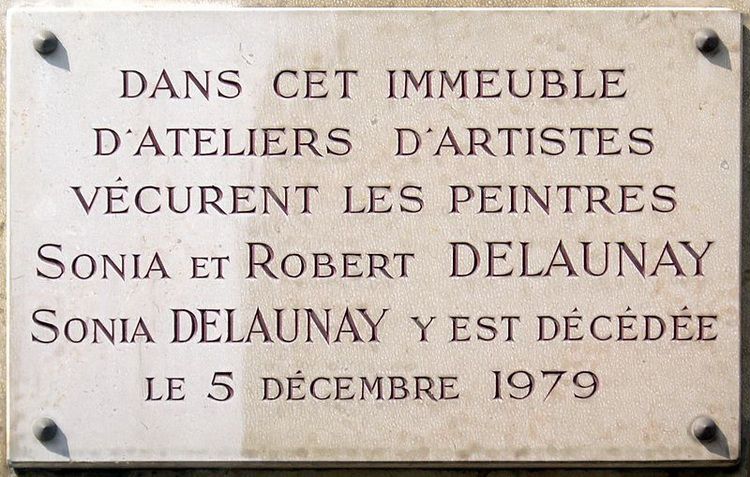

Plaque at 16 rue Saint-Simon where the Delaunay’s lived and where Sonia died.

Delaunay’s painting Coccinelle was featured on a stamp jointly released by the French Post Office, La Poste and the United Kingdom’s Royal Mail in 2004 to commemorate the centenary of the Entente Cordiale.

Plaque at 16 rue Saint-Simon where the Delaunay’s lived and where Sonia died

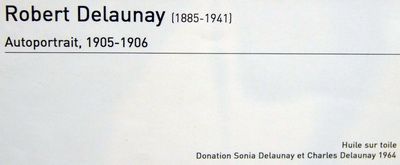

Robert Delaunay (12 April 1885 – 25 October 1941) was a French artist who, with his wife Sonia Delaunay and others, cofounded the Orphism art movement, noted for its use of strong colours and geometric shapes. His later works were more abstract, reminiscent of Paul Klee. His key influence related to bold use of colour, and a clear love of experimentation of both depth and tone.

Early life

Robert Delaunay was born in Paris, the son of George Delaunay and countess Berthe Félicie de Rose. While he was a child, Delaunay’s parents divorced, and he was raised by his mother’s sister Marie and her husband Charles Damour, in La Ronchère near Bourges. When he failed his final exam and said he wanted to become a painter, his uncle in 1902 sent him to Ronsin’s atelier for decorative arts in the Belleville section of Paris.[1] Aged 19 he left Ronsin to focus entirely on painting and contributed six works to the Salon des Indépendants in 1904.[2]

He traveled to Brittany where he was influenced by the group of Pont-Aven and in 1906 contributed works he painted in Brittany to the 22nd Salon des Indépendants, where he met Henri Rousseau.[2]

Delaunay formed a close friendship at this time with Jean Metzinger, with whom he shared an exhibition at a gallery run by Berthe Weill early in 1907. The two of them were singled out by the art critic Louis Vauxcelles in 1907 as Divisionists who used large, mosaic-like ‘cubes’ to construct small but highly symbolic compositions.[3]

Robert Herbert writes: “Metzinger’s Neo-Impressionist period was somewhat longer than that of his close friend Delaunay. At the Indépendants in 1905, his paintings were already regarded as in the Neo-Impressionist tradition by contemporary critics, and he apparently continued to paint in large mosaic strokes until some time in 1908. The height of his Neo-Impressionist work was in 1906 and 1907, when he and Delaunay did portraits of each other (Art market, London, and Museum of Fine Arts Houston) in prominent rectangles of pigment. (In the sky of Couchée de soleil, 1906–1907, Collection Rijksmuseum Kröller-Müller, is the solar disk which Delaunay was later to make into a personal emblem.)”[4]

The vibrating image of the sun in Metzinger’s painting, and so too of Delaunay’s Paysage au disque (1906–1907), “is an homage to the decomposition of spectral light that lay at the heart of Neo-Impressionist color theory…” (Herbert, 1968) (See, Jean Metzinger, Rijksmuseum Kröller-Müller, Otterlo)[5]

Metzinger, followed closely by Delaunay—the two often painting together in 1906 and 1907—would develop a new sub-style of Neo-Impressionism that had great significance shortly thereafter within the context of their Cubist works. Piet Mondrian developed a similar mosaic-like Divisionist technique circa 1909. The Futurists later (1909–1916) would incorporate the style, under the influence of Gino Severini’s Parisian works (from 1907 onward), into their dynamic paintings and sculpture.[4]

Towards abstraction (1908–1913)

Champs de Mars. La Tour rouge. 1911. Art Institute of Chicago.

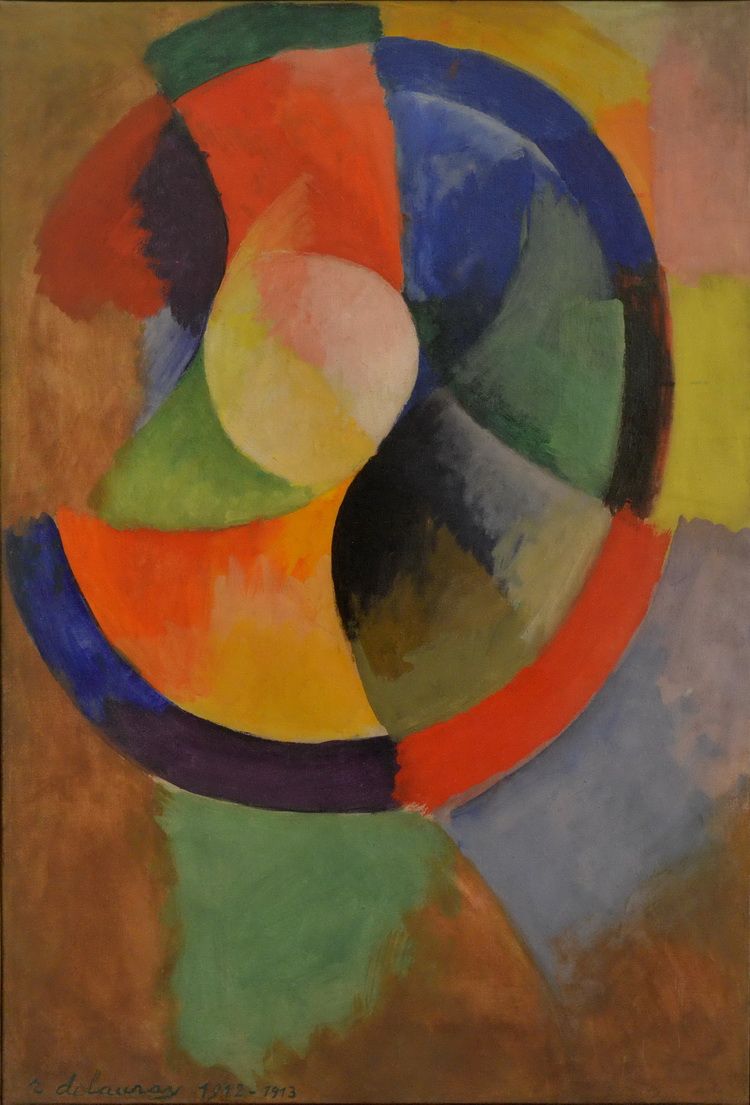

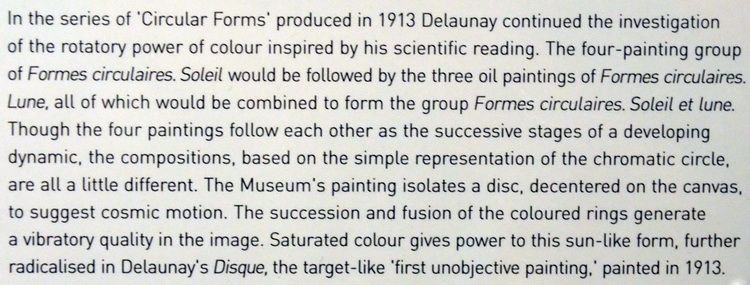

Simultaneous Contrasts: Sun and Moon, oil on canvas painting by Robert Delaunay, 1912–13, Museum of Modern Art, (New York City)

At the prime of his career he painted the known series that included: the Saint-Sévrin series (1909–10); the City series (1909–11); the Eiffel Tower series (1909–12); the City of Paris series (1911–12); the Window series (1912–14); the Cardiff Team series (1913); the Circular Forms series (1913); and The First Disk (1913).

Artist Robert Delaunay is most closely identified with Orphism. From 1912 to 1914, he painted nonfigurative paintings based on the optical characteristics of brilliant colors that were so dynamic they would function as the form. His theories are mostly concerned with color and light and influenced many including the Americans, Macdonald Wright, Morgan Russell, Patrick Bruce, The Blaue Reiter group, August Macke, Franz Marc, Paul Klee, and Lyonel Feininger. Apollinaire was strongly influenced by Delaunay’s theories of color and often quoted from them to explain Orphism. Delaunay’s fixations with color as the expressive and structural means were sustained with his study of color.

His writings on color, which were influenced by scientists and theoreticians, are intuitive and can be sometimes random statements based on the belief that color is a thing in itself with its own powers of expression and form. He believes painting is a purely visual art that depends on intellectual elements, and perception is in the impact of colored light from the eye. The contrasts and harmonies of color produce in the eye simultaneous movements and correspond to movement in nature. Vision becomes the subject of painting.

His early paintings are deeply rooted in Neoimpressionism. Night Scene for example has vigorous activity with the use of lively brushstrokes in bright colors against a dark background. It doesn’t define solid object but the areas that surround them.

Spectral colors of Neoimpressionism were later abandoned, the Eiffel Tower series, were fragmentation of solid objects and their merging with space was learned. Influences in this series were Cézanne, Analytical Cubism, and Futurism. In the Eiffel Tower the interpenetration of tangible objects and surrounding space is accompanies by intense movement of geometric plans that are more dynamic than static equilibrium of Cubist forms.

In 1908, after a term in the military working as a regimental librarian, he met Sonia Terk; at the time she was married to a German art dealer whom she would soon divorce. In 1909, Delaunay began to paint a series of studies of the city of Paris and the Eiffel Tower. The following year, he married Terk, and the couple settled in a studio apartment in Paris, where their son Charles was born in January 1911. At the invitation of Wassily Kandinsky, Delaunay joined The Blue Rider (Der Blaue Reiter), a Munich-based group of abstract artists, in 1911, and his art took a turn for the abstract[citation needed] Delaunay was also successful in Germany, Switzerland, and Russia. He participated in the first Blanc Reiter exhibition in Munich and sold four works. Delaunay’s paintings encouraged an enthusiastic response with Blaue Reiter. The Blaue Reiter connections led to Erwin Ritter von Busse’s article “Robert Delaunay’s Methods of Compositions” which appeared in the 1912 Blaue Reiter Almanac. Delaunay would go to exhibit in February of that year, in the second Blaue Reiter exhibition in Munich and Valet de Carrean in Moscow.

Le Premier Disque, 1912-1913, oil on canvas, 134 cm, 52.7 inches, Private collection.

“This happened in 1912. Cultism was in full force. I made paintings that seemed like prisms compared to the Cubism my fellow artists were producing. I was the heretic of Cubism. I had great arguments with my comrades who banned color from their palette, depriving it of all elemental mobility. I was accused of returning to Impressionism, of making decorative paintings, etc.… I felt I had almost reached my goal”. –Robert Delaunay, “First Notebook,” 1939

1912 was a turning point for Delaunay. On March 13 his first major exhibition in Pairs closed after two weeks at the Galerie Barbazanges. The exhibition showed forty-six works from his early Impressionist works to his Cubist Eiffel Tower painting from 1909–1911. Art Critic Guillaume Apollinaire praised those works of the exhibition and proclaimed Delaunay as “an artist who has a monumental vision of the world.”

In the March 23, 1912, issue of L’Assiette au Beurre, The first published suggestion that Delaunay had broken with this group of Cubists appeared, in James Burkley’s review of that year’s Salon des Indépendants. Burkley wrote, “The Cubists, who occupy only a room, have multiplied. Their leaders, Picasso and Braque, have not participated in their grouping, and Delaunay, commonly labeled a Cubist, has wished to isolate himself and declare that he has nothing in common with Metzinger or Le Fauconnier.”

With Apollinaire, Delaunay traveled to Berlin in January 1913 for an exhibition of his work at Galerie Der Sturm. On their way back to Paris, the two stayed with August Macke in Bonn, where Macke introduced them to Max Ernst.[6] When his painting La ville de Paris was rejected by the Armory Show as being too big[7] he instructed Samuel Halpert to remove all his works from the show.[2]

Spanish and Portuguese years (1914–1920)

At the outbreak of the First World War in 1914 Sonia and Robert were staying in Fontarabie in Spain. They decided not to return to France and settled in Madrid. In August 1915 they moved to Portugal where they shared a home with Samuel Halpert and Eduardo Viana.[8] With Viana and their friends Amadeo de Souza Cardoso (whom the Delaunays had already met in Paris) and José de Almada Negreiros they discussed an artistic partnership.[2][9] First declared a deserter, Robert was declared unfit for military duty at the French consulate in Vigo on June 13, 1916.[2]

The Russian Revolution brought an end to the financial support Sonia received from her family in Russia, and a different source of income was needed. In 1917 the Delaunays met Sergei Diaghilev in Madrid. Robert designed the stage for his production of Cleopatra (costume design by Sonia Delaunay). Robert Delaunay illustrates Tour Eiffel for Vicente Huidobro.[2]

Paul Poiret refused a business partnership with Sonia in 1920, citing as one of the reasons her marriage to a deserter.[10] The Der Sturm gallery in Berlin showed works by Sonia and Robert from their Portuguese period the same year.[2][11]

Return to Paris and later life (1921–1941)

After the war, in 1921, they returned to Paris. Delaunay continued to work in a mostly abstract style. During the 1937 World Fair in Paris, Delaunay participated in the design of the railway and air travel pavilions. When World War II erupted, the Delaunays moved to the Auvergne, in an effort to avoid the invading German forces. Suffering from cancer, Delaunay was unable to endure being moved around, and his health deteriorated. He died from cancer on 25 October 1941 in Montpellier at the age of 56. His body was reburied in 1952 in Gambais.[2]